Paul Werder never imagined a simple gesture of kindness could unravel so many lives.

The retired banker was driving to his investment property on Pittsburgh’s North Side in August when he passed a man lying on his side. His body lay slung across the sidewalk, his head in a patch of weeds, feet near the street.

The man looked unconscious, and Werder, 73, of Elizabeth Township wondered if he had been hit by a car.

Werder parked his dark-gray Chevy pickup in the city’s Brighton Heights neighborhood and hopped out, leaving his keys in the ignition, to see how he might help.

Since retiring, Werder had stayed busy. An eternal optimist, he loved to be outdoors. He spent time keeping up his property in the city. And his youngest daughter was getting married in less than six weeks.

Things were going well for Werder. But his penchant for helping others proved to be his undoing.

Later, after the gunshots, Werder would learn from police that the man he sought to aid was Angus Sanders, a 47-year-old homeless man who oozed volatility and had spent much of his life battling turmoil and mental illness on the North Side.

The youngest of four brothers, Sanders had spun through a revolving door of prison sentences, grappled with drug use and ended up homeless as he fell through the cracks of society.

But that afternoon, Aug. 7, Sanders was just another person who, in Werder’s estimation, might need a hand.

“Are you OK?” Werder asked the figure sprawled on Goe Avenue. “Can I help you?”

The man suddenly came to, turned to Werder and growled, police said. Then, according to investigators, he whipped out a 9 mm pistol and unleashed a volley of gunfire.

Werder was hit.

“Don’t shoot me — I’m just trying to help you!” Werder pleaded before collapsing to the ground.

But the shooter didn’t listen.

Instead, police said, he perched above Werder and kept firing, striking Werder seven times at point-blank range.

Werder remembers lying on his back on the pavement as he drifted in and out of consciousness.

“Things were getting dark. I knew I couldn’t breathe. And I was fading away,” Werder told TribLive, in his first public comments about the shooting. “I just felt helpless, I felt kind of sad, and then I sort of had this acceptance, like, ‘OK, this is it.’ ”

The chance encounter between two people from starkly different backgrounds has left Werder marveling at how 15 seconds of spontaneous violence sent both men and their families traveling down uncertain and perilous paths.

Long road to recovery

First responders whisked Werder a short distance to Allegheny General Hospital’s emergency room. He woke up hyperventilating in the ambulance. Werder was bleeding heavily. Paramedics didn’t know where all the blood was coming from.

Doctors pumped five units of blood and two units of platelets into him.

Werder’s wife, Yasmin, said his shin bone had been snapped like a stick. Surgeons implanted a plate in his left foot and reconstructed his ankle.

In the nearly five months that followed, Werder recuperated, albeit slowly. The gunshot wounds — in Werder’s feet, legs, buttocks and pelvis — didn’t close for weeks.

The bullets missed Werder’s vital organs but caused nerve damage. At least three bullet fragments remain inside his abdomen, near his pelvis.

Surgical complications and infections, some developing weeks after the shooting, led to further stays at multiple hospitals.

It took Werder four months of aggressive physical therapy — sometimes working for more than three hours a day, multiple days a week — to walk on his own.

Doctors said it could take a year, maybe more, for Werder to recover fully.

Werder said this month that he felt proud of how far he’s come. But he still carries a pair of crutches in the back of his truck, just in case his leg gives way.

“You could look at this whole thing and say it’s bad news,” Werder said. “But it’s not bad news. It’s good news — because I’m here. I have another chance. And it allows me to talk about the people, all of these people, that are out here to help us.”

‘What’s your name?’

The shooting and its aftermath warped parts of Werder’s life. But they didn’t change everything.

Werder, a father of three and grandfather of two, was known for buzzing around endlessly on home-improvement projects since retiring from PNC Bank in May 2020. The covid-19 pandemic had capped a 42-year financial career that included decades of service at Mellon Bank.

In addition to toiling on carpentry or installing kitchen counters, the Penn Hills native kept active with exercise. Werder went regularly to the gym and lifted weights. He was a vigorous swimmer. He loved to take mileslong bike rides on trails near his home in southern Allegheny County.

“Paul could never stay still at home — he always has to have a project,” laughed his wife, 65, who also worked in banking and married Paul in 1987.

Werder doesn’t tinker as much anymore at his Brighton Heights investment property, a 105-year-old house where his son lives. Instead, physical therapy sessions and paperwork fill many of his days.

Though Werder tries to focus on life-affirming details and spend more time with his family, he jokes that he also has become a spokesman for the importance of financial and end-of-life planning.

The shooting triggered a keen awareness in Werder of his own mortality. Before he even left his hospital bed, Werder took to a laptop to finalize his last will, burial details and advanced health care directives.

Werder said he’s trying, though, to keep his gaze set forward.

“I think it’s important to be positive,” he said. “If you kind of give up, if you’re steeped in negativity, it’s just not gonna help you.”

Werder also effusively praises those who, he said, “helped put me back together and stay together.”

“I owe my life to the first responders,” he told TribLive. “I owe my life to the ER doctors and to the folks in the intensive care unit. I really, really do.”

In January, Werder hopes to meet and thank in person each first responder who helped rush him to the hospital. There’s also one Pittsburgh police officer Werder wants to meet, if only to bring a touch of closure to his harrowing experience.

As Werder lay on the sidewalk and the world around him fell dark, the officer, whose name Werder doesn’t know, spoke loudly into his ear: “What’s your name? What’s your name?”

“I could barely speak. … I was probably croaking at this point, but he could get ‘Paul,’ ” Werder said. “I kind of had accepted that was it. Things were dark. And that voice brought me back.”

“At some point, I’d like to meet that officer,” he added. “These people have to deal with some of the worst parts of humanity every day. … But I’m going to ask if the officer who spoke to me remembers what he said.”

A long struggle

Pittsburgh police rushed to the scene of the shooting in the 3700 block of Brighton Road at Goe Avenue.

Investigators said the first officer to arrive approached Sanders, who seemed disoriented, and wrestled the gun from his hands. A second officer shocked Sanders twice with a Taser before handcuffing him.

The run-in with police was only the latest of Sanders’ problems.

Sanders had long been troubled. He started hearing voices in his head as a teenager, his mother, Judy Sanders, told TribLive.

Details beyond that are tough to trace.

Judy Sanders declined to talk about her son’s medications or the details of his psychiatric treatment over the years. She will not say who, or how often, she has called in efforts to get help for her son.

Ben Jackson, an Allegheny County assistant public defender who represents Sanders, did not respond to requests to interview Sanders in the Allegheny County Jail.

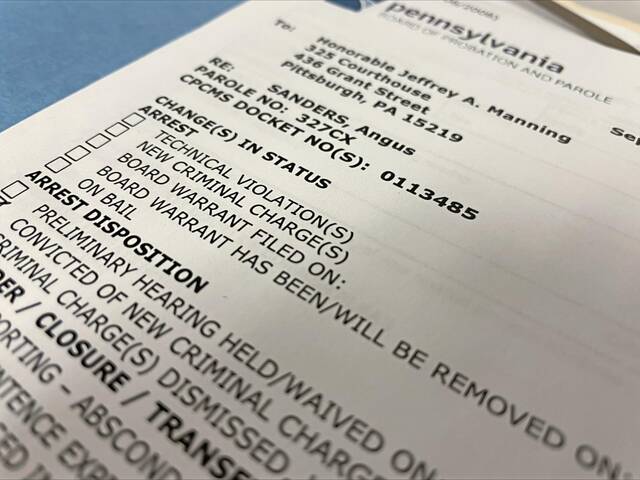

Court records show that Sanders was diagnosed several years ago with paranoid schizophrenia and depression.

“All we can do is call for help. And we’ve done that,” said Judy Sanders, 84, who lives in a five-story apartment building just steps from where the shooting happened. “We’ve called over and over and over and over. He’s been struggling for a long time.”

Sanders dropped out of high school on the North Side in the 11th grade, court records show. Pittsburgh Public Schools did not return phone calls seeking comment on his school record.

Crime followed.

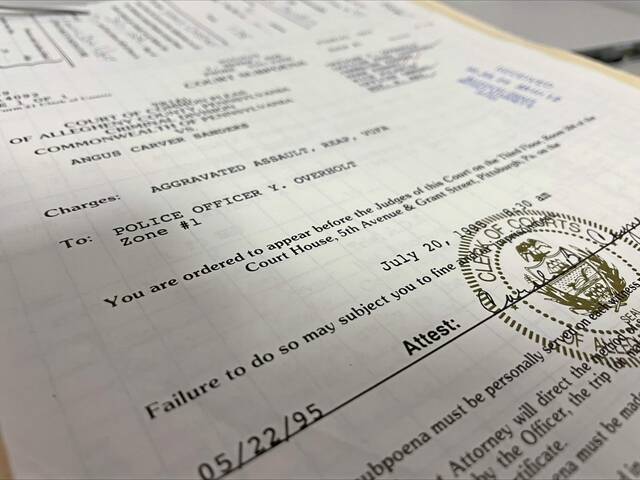

As a juvenile, Sanders was arrested on gun charges, according to court records. At age 18, he fired several shots at two men less than a half-mile from his home in the city’s Perry South neighborhood.

The men were not injured, but a judge handed Sanders his first jail sentence — six to 12 months’ incarceration, court records show. That conviction means he legally is not permitted to carry a gun, Pittsburgh police said.

At age 24, in 2001, Sanders was arrested for a robbery to which he later pleaded guilty. That same year, police caught him trying to deal what they believed was crack cocaine outside a Bellevue pharmacy.

“Everything is fake. It’s all bread,” Sanders told police, according to court records from the drug arrest. “I was just trying to make some money.”

In 2004, Sanders was sent to prison in Pittsburgh, a state Department of Corrections spokeswoman said. He was released five years later.

Sanders went to live in a two-story brick house in McKees Rocks, court records show. Neighbors who lived on Campbell Avenue when Sanders was there told a TribLive reporter they didn’t remember him.

Sanders’ troubles continued.

Two months out of prison, Sanders told police he was smoking crack at least three times a week.

He did two turns in an inpatient rehab program between 2009 and 2011, according to court papers.

On Feb. 3, 2011, just two weeks after Sanders completed his second rehab stint, Pittsburgh police were dispatched to the Ellzey Street apartment in Perry South that Sanders shared with his girlfriend.

Sanders threatened to kill his girlfriend after she accused him of cheating on her, according to a criminal complaint. He went back to jail for making terroristic threats and committing simple assault. The girlfriend has since died, Sanders’ mother said.

Judy Sanders said she isn’t sure if Sanders had been medicated around the time Werder was shot.

“He has a lot of stuff in his mind, making him think somebody’s after him,” she said. “He needs the help really bad. … This should’ve been addressed 10 years ago. I’m not talking about a few days ago.”

In the hours after the shooting of Werder, police found more than 20 pill bottles and numerous loose pills along with Sanders’ possessions in the mulch near a Rite Aid pharmacy across the street from where Werder was hit.

Police also found a 9 mm pistol. The gun had been reported stolen in Swissvale a year earlier.

Neighbors told police Sanders had been living in Brighton Heights for nearly a year, sometimes sleeping near the Rite Aid or hauling a black garbage bag full of his belongings.

When the weather turned frigid, Sanders occasionally slept inside his mother’s car in her apartment building’s off-street parking lot.

As of last week, Sanders remained in custody and had been ordered to undergo a behavioral health evaluation. A judge denied him bail in August.

If Sanders is deemed competent to stand trial, he will appear at a preliminary hearing Jan. 15, officials said.

That hearing already has been rescheduled six times.

Praying for ‘Mr. Paul’

Less than six weeks after the shooting — and just 48 hours after doctors discharged Werder from the hospital — the main thing on Werder’s mind was how he would manage to dance with his youngest daughter, Nichole, at her wedding reception.

A recording of Frank Sinatra crooning “The Way You Look Tonight” filled the Shannopin Country Club ballroom in Ben Avon Heights on Sept. 14.

The bride’s white dress and the matching hijab she wore since converting to Islam contrasted with her father’s navy blue tuxedo — as well as the oversized gray boot that shielded much of his fragile left leg — as the pair twirled around each other, Werder in a wheelchair.

In cellphone footage taken by guests, Werder doesn’t stop beaming.

“I wasn’t that good,” Werder said with a smile. “But we did it. We danced.”

Werder said he has no regrets about the gesture that unknowingly led to the shooting.

“I think if it was something similar, yes, I’d probably stop to check, but I’d probably call 911 first,” Werder said. “If you see someone on the sidewalk, bleeding, you can’t let that go. I don’t think I could let that go.”

Melissa Byrne, Werder’s elder daughter, said her feelings about the shooting and its aftermath are complicated.

“You can want justice, you can want that for our family,” said Byrne, 33, of McKeesport, the middle of Werder’s three children. “But, at the same time, you can have it in your heart to pray for (Sanders), to pray for his family, to pray that he gets the help that he needs.”

She added: “We just want what’s best for everyone involved.”

In that respect, the two families brought together by last summer’s violent act aren’t that different.

Judy Sanders said she prayed for Werder, whom she calls “Mr. Paul,” while he recuperated in the hospital. Her drive to pray, though, did not stop the moment doctors discharged Werder in September.

“I’m hoping maybe something good can come of this,” she said.