Paul Duprex doesn’t fault anyone who’s reluctant to get a covid-19 vaccine.

As director of University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Vaccine Research, Duprex has been awed by the collaboration among academic institutions, pharmaceutical giants, public and private funders and scientists around the globe in the race to defeat the novel coronavirus. He’s elated that the first three FDA-authorized options — Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech and Johnson & Johnson — have made it to tens of millions of people so far. And, as a nearly 30-year virologist, he’s confident in the available shots’ safety and efficacy.

But Duprex also can empathize with those expressing uncertainty and skepticism barely a year since covid-19 began to ravage the globe.

“I have no problem with people who are vaccine-hesitant. … This is a new virus — this is a year old — and these are new vaccines that are less than a year old,” Duprex said. “I totally understand people wanting to ask good questions. I think that’s healthy.”

Duprex encourages skeptics to seek answers from credible sources — not the latest meme spreading around social media. He wants individuals to rely on science and evidence, not misinformation and misplaced fears.

Yet, he and other virologists worry about what will happen if too many people remain vaccine-hesitant for too long.

How do we get to herd immunity?

The stakes are high: If, say, one-third or more of the U.S. population declines to get vaccinated and has not contracted covid-19 severe enough to develop a sufficient antibody response, the coronavirus disease could continue to infect people at rapid and uncontrolled rates, experts say. Estimates suggest at least 70% and as many as 90% of residents will need to get vaccinated to achieve herd immunity, or the point where the disease stops easily spreading across communities.

“The idea is that we might need to have about 70%, 75% of the population with antibodies to reduce the person-to-person spread, just to reduce the burden of disease in general … and to have enough people to block those chains of transmission,” Duprex said.

“That’s the challenge, and that’s the reason we do have to advocate for vaccines.”

As of Friday, just eight U.S. states had vaccinated more than 17% of their residents, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

Pennsylvania ranked 33rd in terms of progress, with about 14% of the statewide population vaccinated, and the general public does not yet have the option to sign up for an appointment amid still-limited supply.

The Biden administration has committed to supplying enough vaccine doses for every American by June, but it remains unclear just how many Americans might refuse them. Duprex said he’s hopeful the percentage of vaccine-hesitant people will dwindle as their friends, family and co-workers get vaccinated and have few to no side effects.

“Then people will be able to look at the benefit and risk and weigh those two things,” Duprex said. “Because the risk of a sore head, the risk of a fever, the risk of a sore arm pales into insignificance compared to the risk of ending up in the hospital in intensive care because you have a really severe case of covid.”

Why some variants matter — but most don’t

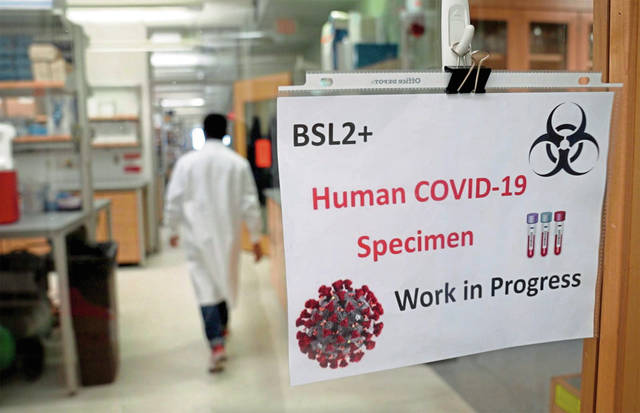

Duprex, a native of Northern Ireland, came to Pitt in 2018, recruited from Boston University to lead the center. He and his research team have been laser-focused on the novel coronavirus since the first samples arrived at Pitt’s biocontainment laboratory in February 2020, days after the disease became known as “covid-19.”

Duprex considers keeping the public informed an important part of his job. That’s why, in addition to daily calls and Zoom sessions with leading researchers, submissions to scientific journals and coordinating lab work, he makes time to speak to reporters, serve as a guest speaker and educate those who approach Pitt’s center seeking information. This month, he appeared on “60 Minutes,” discussing his team’s latest Science journal findings with the chief medical correspondent of CBS.

“There’s no point in just talking to scientists,” Duprex said. “It’s really important to communicate what we’re doing, why we’re doing it and why it matters.”

He’s candid about how much scientists still have to learn regarding covid-19 and its evolution — including the increased focus on emerging variants of the disease popping up in Pittsburgh and worldwide.

“This is a virus that we’re learning a lot about, and what we’re learning is that the virus changes in ways we never could have guessed,” Duprex said. “It’s changing rather quickly, and the word that we didn’t talk about maybe six months ago, three months ago even, was variant.”

Though researchers are paying close attention to such developments, Duprex said, the general public shouldn’t get overly scared when they hear the terms “variant” or “mutation.” The same thing happens with the flu and common cold.

A relatively small number of variants get flagged for research interest, and even fewer are deemed variants of concern, such as the headline-making variants first observed in the U.K., Brazil and South Africa. Variants pose concern only if the mutation has significant effects, like making the virus become more easily transmittable, more aggressive at replicating or more likely to cause severe symptoms and death. Most variants do not pose those risks.

Existing vaccines won’t be altogether ineffective at combating variant cases of covid, because it’s not mutating into an entirely new disease.

Still, if too many variants of concern prevail, then the first generations of vaccines being doled out now may not be as effective at generating antibodies that protect everyone in the long term as the virus evolves, according to Duprex. In other words, one shot or set of shots in 2021 might not be enough.

Duprex points out that, other than the one for measles, few vaccines of any type provide lifelong immunity.

“The vaccines that were developed in 2020 were generated and made against a different virus than the viruses that are circulating at the moment,” Duprex said. “We just have to lie focused on what we have, how to tweak it and how to make second- and third-generation vaccines from what we have.”

Here’s what Duprex had to say about the science community’s latest knowledge about covid-19 — and why we might not ever fully eradicate the disease:

How many known covid variants are out there?

Duprex: There are hundreds of thousands of different variants. Many, many that don’t even have names.

It’s very similar to influenza. The vaccine that people get each year for influenza is different, because the influenza viruses undergoes a process known as drift. It just is slowly changing, drifting, changing its genetic material. And that’s what SARS-coronavirus-2 (covid-19) does as well. Every time a person is infected with the virus, that person produces in their body lots and lots of variants.

Why do some variants rise to the level of concern?

Duprex: It might be able to bind the cell that it’s infecting faster, better or stronger. So it might get in a lot quicker than some of the other viruses … and it will have a head start and become a virus which predominates. We produce all these different sorts of variants and then sometimes those variants change what they do and then they become variants of interest.

Your recent publication in Science discusses revelations about the virus while studying a Pittsburgh patient. Is that a case of concern or interest?

Duprex: It’s absolutely a point of research interest. What that taught us was that the virus was able to use a very interesting way to change itself.

We studied a patient in Pittsburgh who was sick for quite a long period of time. He was being treated for cancer. …

The virus caused what we called a chronic or persistent infection, it ran for over two months, and what happened in that individual is the virus began to change.

We looked at its genetic structure had changed in a really remarkable way, and that opened a whole new avenue of studies.

What we discovered were deletions in the genetic material — not small mutations, but deletions in multiple parts of the genetic material … And once you take something away, the shape really does change. And those deletions were occurring in parts of the molecule that antibodies recognized.

So the coronavirus changes inside the body even while a person is infected?

Yes. Even while someone’s infected, it changes. You have to remember that this a virus, and this is what viruses do. Especially viruses with the genetic material RNA.

Like measles, flu, ebola and the common cold, these are all RNA viruses, and these viruses evolve. They shift their genetic material. And whenever they change their shape, some of the antibodies that used to recognize them might not recognize them anymore.

What roadblocks remain in protecting the public from covid as it evolves?

Duprex: This past year, the science moved quickly, the testing moved quickly, the ramping up of production moved quickly. Now, it’s been hard getting it out to people, and people have questions about when they will get a vaccine.

The second question that people have is how safe are these vaccines because this has happened quickly, are they properly tested, did they go through all of the checks and balances that normally happens with a vaccine? The answer to that question, simply, is yes.

The reason this was fast, fast fast was the phenomenal amount of money that we spent on it. We cannot do that endlessly. We have learned a lot, but we just have to lie focused on what we have, how to tweak it and how to make second- and third-generation vaccines from what we have.

Some of the pharmaceutical companies who used to be competing with each other are collaborating with each other. That’s a good thing. We’ve got more than 80 million people vaccinated. That’s just tremendous in such a short period of time.

But it’s not finished yet. It’s a work in progress, and it will be for quite some time.

In the race against covid, how close are we to the finish line?

Duprex: We need to think about what exactly is the finish line. Is eradication even a possibility?

So, eradicating viruses is very difficult. … We’ve had a vaccine for polio virus for over 65 years, that virus is still not eradicated.

There’s a difference between eradication and control. Can we get it to where enough individuals are vaccinated that we have this herd immunity and we reduce the amount of spread?

If enough individuals are vaccinated that we have this herd immunity where we reduce the amount of spread, reduce the number of people who are infected, we reduce the level of variance. We limit the number of variants that can develop, because we’re just not giving the virus the opportunity to replicate.

We might never eradicate SARS-CoV-2 [the virus that causes covid-19). If you were to ask me to guess, and bet, will we? I would probably say we won’t. But that does not mean that by good social distancing, good masking and believing in the power of the vaccine to produce good antibodies that we cannot control this disease and soon get back to normal.