They came seeking jobs, determined to escape religious persecution, flee the Russians and provide a better life for their families.

The influx of Ukrainian immigrants to the Pittsburgh region covers four distinct waves over the past 150 years. As Russia’s current war in Ukraine rages on, it seems possible that more refugees will arrive in the future, perhaps constituting what could be called a fifth wave.

The region is home to one of the largest Ukrainian populations in the U.S. According to Stephen Haluszczak, author of “Ukrainians of Western Pennsylvania,” as of 2010, about 100,000 Western Pennsylvanians and an estimated 15,000 in the City of Pittsburgh trace their heritage to Ukraine.

Over the years, most settled in the city’s South Side and neighboring Carnegie and McKees Rocks.

Jennifer Murtazashvili, founding director of the Center for Governance and Markets and associate professor at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh, said Ukrainians have been drawn to Pittsburgh by a combination of factors.

“Pittsburgh had a lot to offer to immigrants from Eastern Europe,” she said. “Historically, Pittsburgh had a lot of jobs and was a huge center of employment. They worked in the mines. They worked in the mills. You didn’t need high skills to do that. The skillset that people needed was similar to the skillset they had back in Ukraine, and you didn’t need to speak the language.

“And as the migrants came, there was an Orthodox community, so the churches were established. So Pittsburgh became a magnet for (Ukrainians).”

It’s hard to know exactly how many Ukrainians came here. When many first arrived in America, they identified themselves as Ruthenians, a term used interchangeably with Ukrainian. It caused immigration officials to mistakenly assume they were Russian.

Related

• Ukrainian traditions, roots abound in Westmoreland County

• Feisty Ukrainian resistance explained by Pitt scholars

• Penn Hills man’s Ukrainian family has history of resisting Russian invasions

• Western Pennsylvanians from Ukraine tell their stories

• More on the Russia war on Ukraine

“At the time period we’re talking about, Pittsburgh was a humongous city,” said Eric Lidji, author and director of the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives at the Senator John Heinz History Center. “In the late 19th and early 20th century, Pittsburgh was one of the largest cities (in America) and in the top 10 according to the 1910, ’20, ’30 and ’40 censuses. I think people like me, who grew up here in the ’90s and afterward, we think of it as a mid-sized city.

“If you were coming into the U.S. in the late 1880s, you were coming into one of three ports, most likely New York, Philadelphia or Baltimore — communities that were established. There was not necessarily a lot of opportunity.

“A lot of (Ukrainians) started looking deeper into the country.”

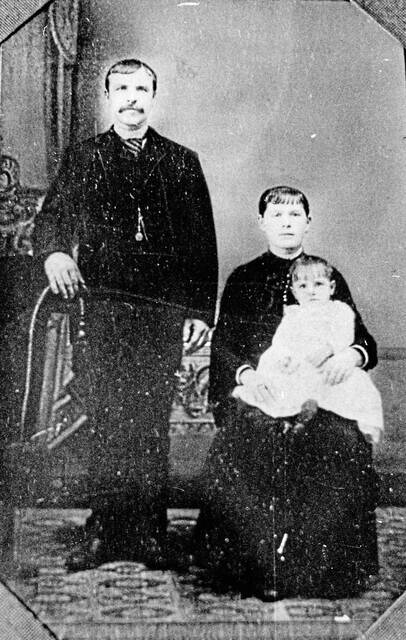

First wave: 1880-1914

The first wave of Ukrainian immigration to the Pittsburgh area was motivated primarily by economics, said Haluszczak, who is also founder and president of the board of directors of the Ukrainian Cultural and Humanitarian Institute in Carnegie.

“People that came to the Pittsburgh area who were of Ukrainian descent were from very poor regions, and most of them were uneducated farmers. They were looking to make money and go back home,” Haluszczak said. “They heard of this ‘shining city on a hill,’ as Ronald Reagan would call it. They came because of the steel mills, coal mines and railroads — they were the biggest attractions at the time. Those were the days when the steel mills and mines employed thousands and thousands.”

But in the early years of the 20th century, escape became another motivating factor. As World War I loomed, Ukrainians, like others in Eastern Europe, wanted to avoid conscription.

The outbreak of war made it difficult for the Ukrainians who came here to get back home. Many never did.

“They wanted to go back to Ukraine, but oftentimes bigger events took place that prevented them from going back home, and they ended up staying here,” Haluszczak said.

One of the more interesting stories surrounding the outbreak of World War I involved a 9-year-old Ukrainian Jewish girl named Bess Topolsky. She was from a town called Skver in central Ukraine and was visiting family here in 1914. When the war broke out after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on June 28, she was stuck here.

Topolsky stayed in Pittsburgh for the rest of her life.

“She was a really interesting figure. She was sort of the last link to the world of Yiddish culture in Pittsburgh,” Lidji said.

Topolsky ran the local branch of the newspaper The Forward, became involved with many Jewish labor organizations such as The Workman’s Circle and served on the city’s Human Rights Commission before her death in 1996.

Ukrainian Christians, Jews feel at home

Ukraine briefly became an independent state in 1918 before becoming part of the Soviet Union in 1922. Over the years, Soviet leaders attempted to eliminate all religious expression.

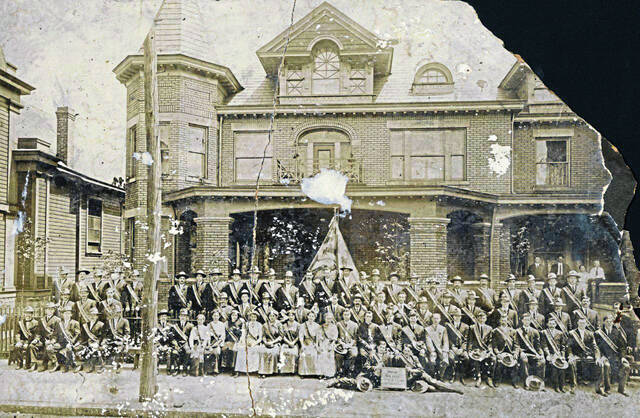

However, Ukrainian Christians and Jews found a home in the Pittsburgh area. At one time, there were 21 Ukrainian Catholic churches, including the first — St. John the Baptist Ukrainian Catholic Church, founded in 1891 on the South Side — and 16 Orthodox churches in the area.

Church, in many ways, became the center of life for many Ukrainian immigrants here and elsewhere.

“It was a place where people could gather and help one another. Reading rooms were built, and there were social services that were developed in those churches,” Haluszczak said.

The story of Ukrainian Jews in Pittsburgh begins in the late 1890s with a congregation founded in the Hill District.

“The congregation was not calling itself Ukrainian because that was not the term being used at the time,” Lidji said. “But that’s where they were all from.”

Lidji said that rather than calling themselves Ukrainian, they referred to themselves using the province or municipality they were from.

From 1899 on, Lidji said, a large number of Ukrainian Jewish organizations formed in the city. Much of the influx was driven by a 1903 massacre in Kishinev in which 49 Jews were killed and 92 were injured.

Second wave: 1920s

The years between 1917 and 1921 saw the murders of between 50,000 and 200,000 Jews in Ukraine in the aftermath of World War I. Many more Jews were victims of violence and loss of property.

“In general, all of the immigration from Europe was people fleeing oppression or coming toward a better opportunity or some combination of the two,” Lidji said. “As these incidents happen, you’ll get large groups of people leaving, and often their identity is at the provincial level, not even the national level.

“So in Pittsburgh, there was a congregation founded just of people from Volhinya. There was another just of people from the province of Pedolia.”

Haluszczak said after Ukraine’s brief period of independence between 1918 and 1922, more Ukrainians wanted to come to the United States. Many already had family in Pittsburgh. And according to Haluszczak’s cousin, the Rev. John Haluszczak of St. Vladimir’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church on the South Side, Pittsburgh reminded them of home.

“The topography is very similar,” he said. “I’ve been to western Ukraine, and the hills are very similar and the land is similar. So I think they probably felt comfortable. In Pittsburgh, you can have an enclave of people. You can have everybody in one valley, and you can have your church there and you can feel like you’re at home.”

Third wave: Post WWII

As World War II ended, Ukrainians saw a future of continued rule by iron-fisted and ruthless dictators. More Ukrainians were now trying to get to America.

The post-World War II Ukrainian immigration wave was political, not economic, said Andrew Nynka, publisher of the Ukrainian National Association’s The Ukrainian Weekly and Svoboda — the world’s oldest continuously published Ukrainian language newspaper. It’s based in Parsippany, N.J.

“People, like my grandparents, were fleeing,” he said.

Nynka said his grandparents ended up in displaced persons camps before making it to the United States. Though not as large as previous immigration waves, about 300,000 displaced people eventually made it to America during the 1950s — including the parents of Walt Sluzynsky.

“My parents came over after World War II, and they had the choice of coming to America, Brazil, Australia or going back to the Ukraine,” said Sluzynsky, 67, of Monaca. “But my dad said if he went back to Ukraine, he’d wind up in Siberia. So that was not an option. He decided to come to the United States, which I’m thankful for. I am a first-generation Ukrainian born here.”

Fourth wave: Post-USSR and beyond

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 paved the way for Ukraine to become its own independent state again, but it also created uncertainty and economic depression. It inspired a fourth wave of immigration to Pittsburgh.

“In the ’90s, the universities were something that attracted highly educated Ukrainians to Pittsburgh in STEM fields, for example. Pittsburgh’s been a huge magnet for them,” Murtazashvili said.

Stephen Haluszczak said he wouldn’t be surprised to see a fifth wave of immigrants come to Pittsburgh as the current war wears on. More than 1.2 million Ukrainians have fled their country in about a week, according to the U.N.

“I’m hearing more about the potential for refugees (here),” Haluszczak said. “With the overwhelming number of refugees straining countries in Eastern Europe now, it just may happen.”

Murtazashvili said Ukrainian scholars are likely to find the idea of coming to the U.S. appealing but currently have a lot of options in Europe.

“With the Ukrainian passport, you can go a number of places without a visa, and because Ukraine shares borders with the European Union, Ukrainians actually are allowed to travel to EU countries,” she said. “So they have much more freedom to travel. I imagine some will want to come to the United States eventually, maybe some that have family ties here will want to come sooner rather than later.

“I don’t think we should immediately expect a huge wave of Ukrainian immigrants to Pittsburgh. But it would be nice if we had them.”