It takes Kathy Younkins just a few minutes to walk to her neighborhood Rite Aid. The 67-year-old has picked up her prescriptions at the company’s Harrison location since the 2000s.

But now the Philadelphia-based pharmacy empire is crumbling.

The company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy earlier this month, blaming “the rapidly evolving retail and health care landscapes.”

Any of the roughly 1,200 Rite Aid stores, including more than 300 in Pennsylvania, that aren’t sold within a few months are expected to close. About 31,000 workers have lost or will lose their jobs.

In the Pacific Northwest, reported Bloomberg on Thursday, rival CVS Health Corp. put in a bid to buy Rite Aid stores in Washington, Oregon and Idaho. The company also bid for prescription patients records from Rite Aid. But that move, Bloomberg reported, is aimed at giving CVS more presence in that region.

There have been no bids reported for Rite Aid stores elsewhere.

Already, stores shutting down are in Apollo, West Kittanning and Rostraver as well as Pittsburgh’s Carrick, Lawrenceville and Oakland neighborhoods, according to court records.

The losses will go beyond where people pick up their pills, though switching pharmacies is an inconvenience in its own right. Customers like Younkins have come to trust their pharmacists, “and now you have to go build a relationship with a new one,” she said.

America’s drug stores are in upheaval, buckling under the weight of pharmacy benefit managers, according to pharmacists, industry experts and lawmakers interviewed by TribLive. These groups act as middlemen between drug manufacturers and insurers or employers.

The idea is they can pool buying power and tamp down drug costs. Critics say pharmacy benefit managers leverage their position to underpay pharmacies and rake in profits.

Greg Lopes, a spokesman for the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, an industry group representing benefit managers, refuted those claims.

“It makes no sense to blame (pharmacy benefit managers) for pharmacy closures,” he said. “There are many factors for pharmacy closures, including online pharmacy options and demographics.”

While independent pharmacy closures — of which there have been many — have hyper-local impacts, the unraveling of Rite Aid is disrupting markets on a massive scale. That’s especially true for Western Pennsylvania, one of the company’s strongholds.

“We’re getting 50 prescriptions a day-or-so that are transferred,” said Jay Adzema, owner of Adzema Pharmacy in McCandless.

But $50 to $100 losses on certain prescriptions mean volume could become a drag on business. Adzema Pharmacy no longer dispenses GLP-1 drugs, such as Ozempic, because of their terrible margins. Even then, Adzema has drawn down a “significant amount” of his personal savings to keep the store afloat.

“We would never turn a patient away, and in the past few years with all this craziness, we’re starting to say, ‘no, we can’t do this,’” he said. “It’s a change in the industry for the worse.”

Some communities, particularly rural ones, will lose their sole pharmacy if Rite Aid leaves and no company takes its place. This would create what’s known as pharmacy deserts, typically defined as a 1-mile radius in urban areas and 10-mile radius in rural areas without access to a drug store.

Scottdale is slated to be without a pharmacy, putting it on the edge of desertification. Residents who rely on the town’s Rite Aid will have to go to Mt. Pleasant, Connellsville or New Stanton, each at least a 10-minute drive away.

“It is the only pharmacy in our town, and a large portion of our residents use the store,” said borough Manager Stacey Coffman. “Some of our residents may not even be able to travel, and where does that leave them?”

Residents in Derry could face a similar problem. If Rite Aid stores close there and in neighboring Latrobe, they might need to travel more than 20 minutes for pharmacy services at chain stores along Route 30.

Help could be on the way, at least in Westmoreland County.

County Commissioners Sean Kertes and Doug Chew told TribLive they plan on approving a new contract next month with the county’s transit authority. It would expand the destinations that can be reached through the authority’s Medical Assistance Transportation Program, giving eligible passengers rides to grocery stores and pharmacies.

Mail-order services also could help fill the gap Rite Aid is leaving, according Sophia Herbert, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Pharmacy. But they’re no substitute for the full-range of services pharmacists can perform, like giving vaccines and advising patients on medication use.

Benefit managers, killer of pharmacies?

Pharmacy benefit managers have been around since the 1960s. Today, the largest are Express Scripts, Optum Rx and CVS Caremark, the only of the three to be directly integrated with a pharmacy chain. CVS stock is up 33% this year, even as Rite Aid collapses and Walgreens prepares to go private, a jump partly driven by investor confidence in its benefit manager business.

For most in Western Pennsylvania, though, these firms were an afterthought until a string of independent pharmacy closures last year.

The state took action shortly after. A bill signed by Gov. Josh Shapiro in July restricts several common industry practices that jack up profit margins for benefit managers, including clawbacks, where they charge pharmacies additional fees after a drug is dispensed. Implementation is ongoing.

“I recognize that for some pharmacies my legislation sadly came too late, and my hope is that it will be enough to still save others as we consider even further reforms and wait on the federal government to take action,” said State Rep. Jessica Benham, D-South Side, who introduced the bill’s House version.

President Donald Trump signed an executive order Monday promising to “cut out the middlemen” in medication sales by establishing a mechanism for patients to buy more drugs directly from manufacturers. Benefit managers also faced a lawsuit over insulin prices under the Biden administration’s Federal Trade Commission, though the agency paused that effort last month.

Back at the state level, spread pricing could be Benham’s next target, she told TribLive. This occurs when benefit managers charge insurers or employers more than they reimburse pharmacies and pocket the difference.

A May report from the Washington, D.C.-based Phoenix Center cited by Lopes, the benefit manager spokesman, noted employers can contractually restrict or eliminate spread pricing but often don’t because it increases cost predictability. And a report funded by the big three benefit managers and released in April shows they keep less than 2% of the fees they receive, giving the rest to pharmacies.

Benham also is looking into a single benefit manager for the state’s Medicaid patients, a system that has found success in other states.

But those changes won’t arrive for years, if at all. And if major chains can’t hang in this climate, what chance do their small-town counterparts have?

Ed Christofano, owner of Hayden’s Pharmacy in Donegal, Mt. Pleasant and Youngwood, doesn’t hate his odds.

“Rite Aid being such a large corporation, they’re not nimble enough and agile enough to make the necessary adjustments as we have done to stay alive,” he said. “When you’re an independent pharmacy owner-operator, you’re controlling all your expenses on a line-by-line basis.”

He’s hardly getting rich, though. And day-to-day challenges have kept him from making upgrades, like new delivery vehicles or improvements to his stores.

“I just want to be able to grow, prosper and thrive as a business,” he said. “I would rather focus my energy there … versus constantly being on the defensive and reactive to the lack of the reimbursements.”

Preparing for the end

Rite Aid’s financial woes manifested as barren shelves for months, tipping off customers the end was near. Online chatter by employees suggests they were tasked with spreading out product in some areas and consolidating it on others to give the illusion of well-stocked stores.

That didn’t fool customer Michael Burns of Derry, who was hardly surprised to learn of Rite Aid’s bankruptcy.

“We’ve been expecting it,” he said.

Now it’s official.

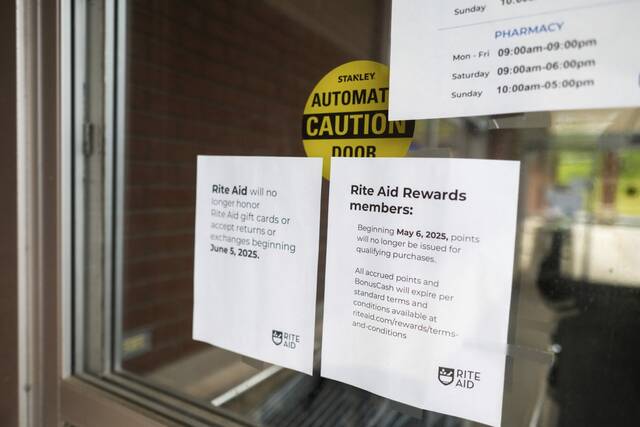

Rite Aid assured customers in a recent letter that they can access pharmacy services in-store and online for the next few months. The company is “working to facilitate a smooth transfer of prescriptions to other pharmacies,” the letter continued.

The chain noted in court filings a quick sale is needed to reduce the number of customers jumping ship and to preserve the value of its assets.

It also warned of challenges for other pharmacies, which “must receive legal prescriptions, integrate them into their systems, acquire a sufficient supply of medication to fill the prescriptions and be staffed to handle the additional prescriptions.”

Melissa McGivney, a pharmacy professor at Pitt, urged Rite Aid patients to call and name a new preferred pharmacy well before their next refill. The next step, she said, is to check in with the new pharmacy.

“Get to know the people,” she said. “Give them a chance, and I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised.”

Customers can expect delays as pharmacies deal with more transfers than usual, according to Herbert, the assistant professor at Pitt. Moving to a new pharmacy typically takes a day or so. It may take a few days under these circumstances.

All this may be a “pain” and a “hassle,” as New Kensington resident Bill Humlan, 70, put it while leaving Rite Aid in Lower Burrell. He’s considering a switch to the closest Giant Eagle pharmacy. But it also can be an opportunity.

“It can be a time for people to think about, if they are going to switch pharmacies out of necessity, what is going to be best for me going forward?” Herbert said.

Staff writers Renatta Signorini and Jeff Himler contributed to this report.