Christine Siess has never forgotten the uncle she never knew.

Thousands of miles and an ocean away, Aldwin van der Velden also remembers Siess’ uncle.

Norman Frank Kajut, a New Kensington native, is among the thousands of American World War II service members van der Velden and his fellow Dutch citizens still honor as their liberators.

Siess, 74, of Lower Burrell was born more than four years after Kajut died Feb. 10, 1944, when the B-17 bomber on which he was a radio operator was shot down over the Netherlands. Kajut was 23. Siess learned about her uncle from her mother, who kept his photo in their home.

“She always got emotional,” Siess said. “She said he was the best brother.”

Van der Velden, 50, lives in Waalwijk, a city about 60 miles south of Amsterdam. Three times a year — on Kajut’s birthday, the anniversary of his death and Memorial Day — van der Velden makes the nearly two-hour drive south to the American cemetery in Margraten where Kajut is buried.

“They must not be forgotten,” van der Velden said. “They paid the highest price for our freedom. The least I can do is honor them by visiting their graves.”

Called to serve

Kajut was born on Dec. 11, 1920. He was the only son of Frank and Cecilia Tuchnowski Kajut. The family’s home, at 832 Second Ave. in New Kensington, is no longer there.

He had two sisters — Siess’ mother, Irene D. Paladino, who died in July 2010 at 91, and Geraldine Helen Wierzbicki, who was 79 when she died in August 2004.

A third sister, Eleanor, died shortly after birth, Siess said.

A student of New Kensington High School, Kajut grew to 6 feet, 1 inch tall and weighed 161 pounds, according to his Selective Service registration. He had blue eyes and brown hair.

He worked for Alcoa and then Union Spring, a spring manufacturer, before being drafted in July 1942.

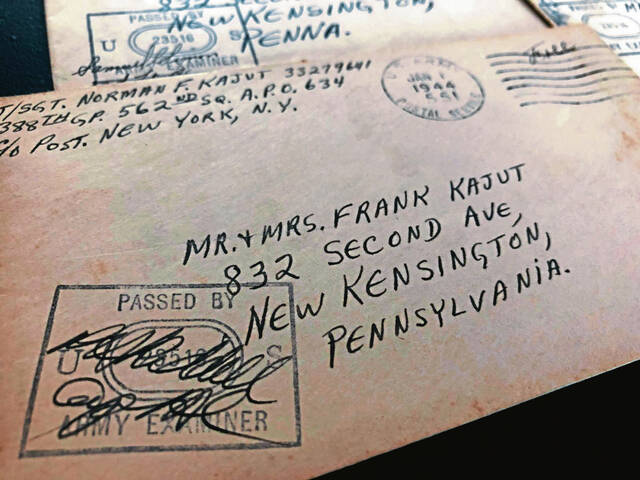

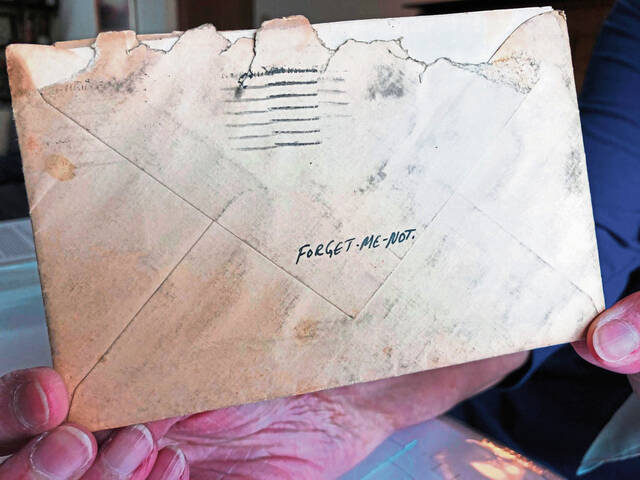

Siess, who was born in 1948, learned of her uncle not only from her mother but also from more than 100 letters he wrote to his family while in training in the U.S. and overseas. On the back of most of the envelopes he sent while in training, he wrote, “Forget Me Not.”

“He was very dedicated to his family. He loved his family. He loved his parents and his sisters,” Siess said. “He had a girlfriend and thought about getting married.”

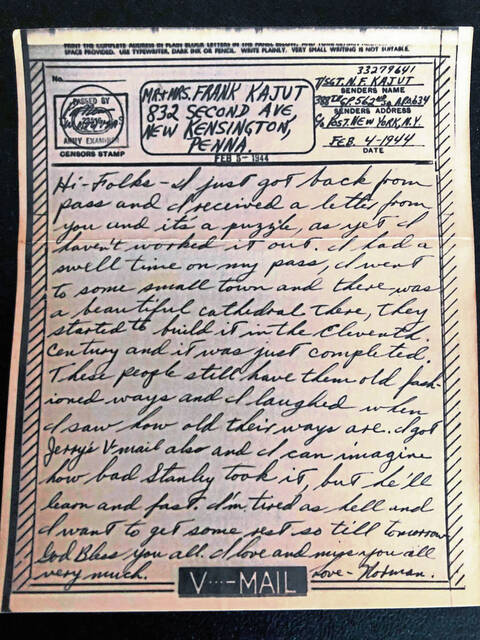

In one of his last letters, dated Feb. 4, 1944, six days before his plane was shot down, Kajut wrote about having been on pass and visiting a small town where construction of a cathedral started in the 11th century was just being completed.

“These people still have them old fashioned ways and I laughed when I saw how old their ways are,” he wrote on the tiny letter called “V-Mail,” the “V” standing for victory.

“I’m tired as hell and I want to get some rest so till tomorrow,” is how he ended the letter. “God bless you all. I love and miss you all very much.”

‘Bail out, hit the silk’

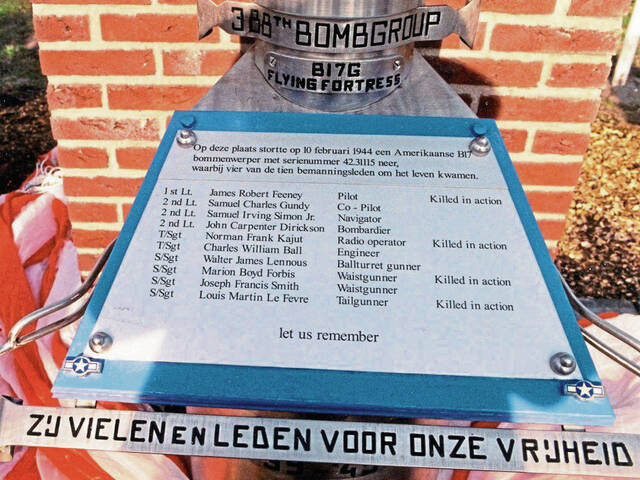

A technical sergeant in the Army Air Corps, Kajut was the radio operator on a B-17 nicknamed “Hell’s Belles.” It was returning to base in Knettishall, England, from a bombing mission over Brunswick in Germany when it was attacked by German fighters and crashed in a field near Uitgeest, a town about 20 miles north of Amsterdam.

Kajut was one of four from the 10-member crew who died in the crash. The remaining six were captured by the Germans and held as prisoners of war. They eventually returned home.

The co-pilot, 2nd Lt. Samuel C. Gundy, was among the POWs. He described the crash to Siess in a September 1999 email. The last surviving member of the crew, he lived in Reading and was 92 when he died on April 23, 2010.

Gundy said their B-17 was attacked by a large force of German Focke-Wulf 190 fighters.

“It seemed they had all picked out our plane,” Gundy wrote. “We were badly crippled, fell out of formation and Jim (pilot 1st Lt. James Robert Feeney, killed in action) and I were struggling to keep the plane in the air, but the effort was futile.”

Gundy said he made a check, and every man was OK.

“We knew we were going to have to bailout eventually, but the port wing began to tear open at the wing root,” he wrote. “Then flames spewed out of the tear in the wing, Jim kept trying to hold the plane, and I told the crew to ‘Bail out, hit the silk, we are on fire and she’s going to blow.’ ”

Gundy said the craft went into a “terrible spin,” the force making it impossible to move. “Then, thankfully, the plane exploded, blowing us out,” he said.

In his report upon returning to the States, Gundy said that, just before the crash, Kajut told Feeney he was going to send out an “urgency call” in case they had to ditch. He last saw him in the plane.

“It is my belief that Sgt. Kajut was sending out a call at the time the bail out order was given and did not hear the order to bail out,” Gundy wrote in his report.

Gundy said he believes that Sgt. Joseph Francis Smith, a waistgunner who was among the POWs, tried to get Kajut out but could not open the radio room door.

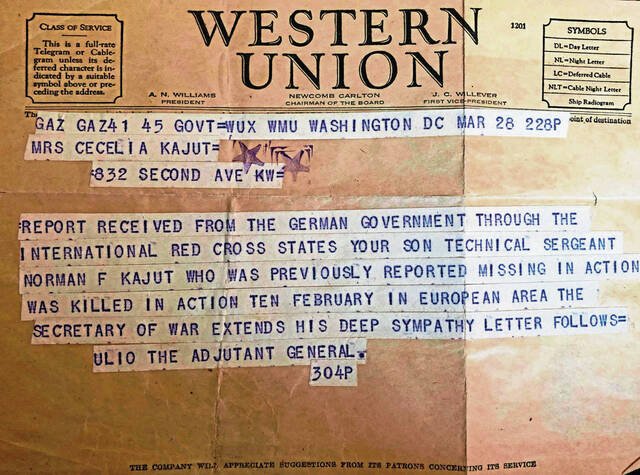

Kajut’s family was first told he was missing before receiving word in a Western Union telegram more than a month later that he had been killed in action. The report came from the German government through the International Red Cross.

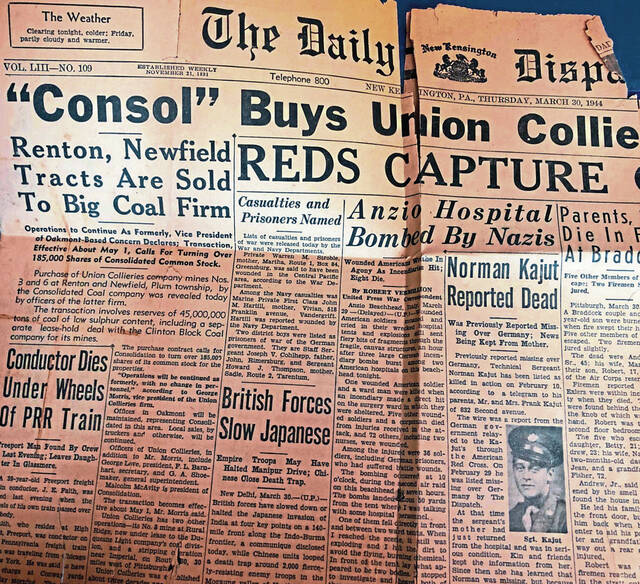

News of his death made the front page of The Daily Dispatch, New Kensington’s newspaper, on March 30, 1944.

At rest overseas

According to a September 1946 letter from the War Department to Frank Kajut, his son originally was buried in a temporary cemetery established near where he died and later “moved to a more suitable site where constant care of the grave can be assured by our Forces in the field.”

His remains were then known to be buried at the U.S. military cemetery in Margraten.

Frank Kajut was given the opportunity to have his son brought home for burial. Siess believes that, after her grandmother had died from cancer at age of 52 in May 1944, it was too much for her grandfather to deal with, so he chose to leave her uncle buried in Margraten.

Frank Kajut was 80 when he died in April 1968.

The cemetery was constructed in November 1944 for the U.S. Ninth Army. In 1949, the Army turned it over to the American Battle Monument Commission, which manages all overseas cemeteries.

Today, Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial is the resting place for 8,301 American service members who died during World War II. In addition, there are 1,722 names on its walls of the missing — those whose bodies were never recovered.

Siess is the only member of her family to visit her uncle’s grave. She was there in February 2001, a few days after participating in the unveiling of a monument to her uncle’s B-17 crew near the crash site on the anniversary of the crash.

A plaque on the monument lists the names of all 10 members of the crew and says, in English, “Let us remember.”

She spoke with people who remembered seeing her uncle’s plane go down.

“It was pretty emotional,” she said. “The people there in the Netherlands are so very nice. They’re just very grateful the men were there and they were liberated. They’re free because of the Americans.”

Never forgotten, always honored

The only American war cemetery in the Netherlands, Netherlands American Cemetery also is unique for its grave adoption program, which dates to 1945. Adopters were supposed to regularly visit the adopted grave and, if welcome, keep in touch with the next of kin in the U.S.

Every grave was decorated with flowers for its first Memorial Day in 1945. A year later, all graves — 18,764 at the time — had been adopted.

Currently, every grave is adopted and there is a waiting list, according to the Foundation for Adopting Graves at the American Cemetery Margraten, which succeeded the original citizens committee. The names of the missing also are adopted.

Stichting Adoptie Graven Amerikaanse begraafplaats Margraten from Evisual on Vimeo.

A 2012 book by Peter Schrijvers, “The Margraten Boys: How a European Village Kept America’s Liberators Alive,” provides an extensive history of the adoption system.

Siess said she knew of the cemetery’s adoption program when she visited in 2001 but didn’t inquire more about it, having been fairly overwhelmed by the trip.

Van der Velden said he adopted Kajut’s grave and two others — Robert B. Youngs and Leon J. Engle — in 2005. He has not been able to find any information on Youngs and Engle.

Van der Velden said he adopted one for himself and one for each of his daughters: Sanida, 27, and Morrison, 21.

He did so, he said, “to honor the American fallen heroes for our freedom.”

Van der Velden’s parents had taken him to the cemetery when he was a boy.

“I saw the white crosses and the names on the walls from the still missing young heroes. This was so impressing to me. My father told me about their sacrifices for our freedom,” he said. “That moment, I decided to become a soldier so I also could fight for the freedom of other people.”

Van der Velden served from 1993 to 1994 in the Bosnian War with the United Nations as a peacekeeper, one of the “Blue Helmets,” he said. He is unable to work because of post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Although I struggle every day with PTSD, I never regretted the choice I made,” he said.

‘An extension of us’

Siess said she did not become aware that someone had adopted her uncle’s grave and that it was possible to know who had done so until finding that information online in 2021.

Van der Velden said a member of the cemetery board called him in June 2021 about someone being interested in learning who adopted her uncle’s grave. He agreed to share his contact details, and he and Siess began writing to each other.

“His emails are so touching,” she said.

In August 2021, Siess sent van der Velden a booklet of information about her uncle and the other crew members.

“I noticed that one of the crew members, Louis Martin LeFevre, also was buried in Margraten. So, every time I go to the cemetery, I’m bringing flowers for him also,” he said. “That’s the least me and my family can do. They are not forgotten.”

Siess said she would like to go back to the Netherlands.

“But with the war (in Ukraine) and covid and my health issues, it may not happen,” she said. “I certainly would love to go back, and especially meet Aldwin, too.”

Siess said that when van der Velden visits her uncle’s grave, he brings yellow roses, representing connectedness.

“It’s just so thoughtful. Our family so much appreciates that,” she said. “I feel Aldwin is an extension of us. We can’t get to the cemetery. It’s nice he can be there.”