Confronting financial woes exacerbated by the pandemic, the Jewish Association on Aging announced Thursday that it plans to close Charles Morris Nursing & Rehabilitation Center in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood.

The nonprofit nursing home — among the highest-rated such facilities in Western Pennsylvania — is set to shut down permanently on Jan. 12, leaving two months for its 50 current residents to relocate and 104 employees to find new jobs, either within the JAA organization or elsewhere.

“This is just devastating to the community,” said Robert Wyner of Monroeville, whose 96-year-old mother Rose Wyner has been a resident at Charles Morris since September 2018. “My first thought was my mom’s health and well-being. Change for seniors is not easy. I am beside myself. I am afraid to tell her.”

Deborah Winn-Horvitz, president and CEO of the Jewish Association on Aging, which owns and runs the nursing home, described a trifecta of crises converging to prompt the closure: years-long underfunding of Medicaid reimbursements; a statewide shift toward at-home and community-based care; and the pandemic hiking expenses while causing revenue to plummet.

“There have been a lot of tears today because everyone does feel like a family here,” Winn-Horvitz told the Tribune-Review on Thursday afternoon, shortly after notifying staff and residents of the looming closure. “We have just been starting to talk to our families and residents and staff today, and it’s been a very, very difficult, it’s a very painful decision for us to make.”

The Charles Morris nursing home has no active cases of covid-19, continues regular testing for the virus and has recorded a total of 14 resident cases, JAA officials said. Seven residents who tested positive for covid-19 have died, including some who were on hospice care with other serious health problems. Fifteen staffers tested positive since April and all recovered and are now healthy.

Andrew Stewart, chair of the JAA’s board of directors, said it was the nursing home’s financial situation that “became untenable.”

“The administration and board have explored every available option for our organization, including downsizing, mergers and affiliations,” Stewart said in a statement. “However, we have not been able to overcome the shortfall that the gap in Medicaid funding has delivered to our doorstep. As painful as this is, we are confident that the tentative decision to close Charles Morris would allow us to meet new challenges head on and preserve our mission in caring for seniors in our community.”

Hoping for a smooth transition

The JAA will be working with residents and their families in hopes of easing the transition for residents, particularly those with high needs such as those living with dementia.

“This is all driven by resident choice,” Winn-Horvitz said. “Our obligation is to provide them high-quality options from which they will make a decision … after that, our obligation is to make sure that it’s a very, very smooth transition and that we know that we’re comfortable that all of their needs are going to be met at wherever they are going to.

“The good news is, because of covid, there are other beds open in other facilities, and we know who the other quality providers are.”

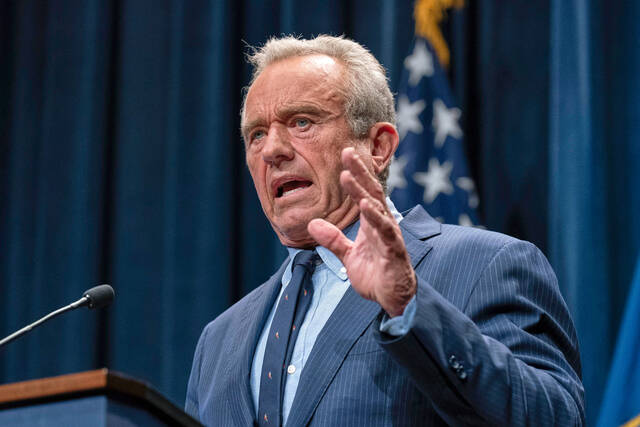

Robert Wyner, who got a call from Charles Morris officials notifying him of the closure on Thursday morning, said he feels bad for the hardworking staff who have cared for his mom. In some cases, the JAA’s leaders hope, long-term employees may be able to follow residents to their new accepting facility and continue caring for them.

“It is our hope that some of our staff, our long-term employees who know our residents very well, will be able to go with them to the accepting facility,” Winn-Horvitz said. “We know that one of the challenges again that’s out there in the field is staffing.”

For residents with family in places such as the North Hills or South Hills, it could be an opportunity to relocate “closer to home,” she said.

“We know that there are some who may go home to family,” Winn-Horvitz said. “Some of these residents, we believe, we will be able to keep in-house in our continuum in one of our other residential lines of business.”

Apart from the shuttering nursing home, the JAA’s senior care network spans assisted living communities, personal care homes, outpatient therapy and medical services, meal delivery and hospice care. The JAA has “a number of internal openings” and will work to help employees find other roles at the organization when possible.

Federal coronavirus aid ‘not enough’

The JAA received a $4 million Payment Protection Program assistance that helped it avoid laying off any of JAA’s 500 employees up to this point.

“We’re very thankful for the government funding that we received. Unfortunately, it’s not enough. It’s not enough for any of the providers who are out there,” Winn-Horvitz said. “No. 1, we can’t count on additional government funding coming in, and No. 2, some of the money that has been provided to nursing home operators, senior care providers, we are going to have to pay back.”

Charles M. Morris Nursing & Rehabilitation Center’s roots date to 1906, when the Jewish Home for the Aged opened in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. The Jewish Home for the Aged moved to the Browns Hill Road campus in 1933, and the center opened as Charles Morris on the same site in 1998. Its campus sits just east of Browns Hill Road and north of the Monongahela River, a short drive across the Homestead Grays Bridge to the Waterfront shopping area.

The nursing home boasts among the best ratings for quality doled out by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, receiving an overall five-star rating, or “much above average,” with “much above average” rating for health inspection issues and “above average” for staffing. It has not had any penalties or fines issued and no complaint-based inspections in recent years, CMS records show.

Prior to covid-19, “we had not really contemplated closure,” Winn-Horvitz said.

The pandemic turned out to be “the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back,” Winn-Horvitz said.

But the board had been exploring various options in response to financial challenges such as underfunding for Medicaid, which most nursing home residents rely on. Medicare only covers up to 100 days in a skilled nursing facility, after which residents must pay $8,000 to $12,000 a month out of pocket or shift onto Medicaid — which reimburses providers at lower rates than Medicare, short-term care and private payors.

Pennsylvania’s Medicaid reimbursement rates have remained flat for six years.

Charles Morris nursing home’s gap in costs of services versus Medicaid funding totaled $4 million in the 2019-20 fiscal year, more than double the size of the gap five years ago. Statewide, the estimated Medicaid funding shortfall at nursing homes totals more than $630 million.

Nonprofits such as JAA tend to bear the brunt of the burden, with nonprofit and religious facilities accounting for 60% of the statewide Medicaid funding gap, according to figures cited by JAA as well as industry advocacy groups.

Short-term rehabilitation stays typically help nursing homes make up some of the difference. When hospitals and individuals began postponing surgeries because of the threat of covid-19, the nursing home’s census kept dropping.

“Those referrals really dried up … during covid, when elective procedures went away,” Winn-Horvitz said.

The nursing home is licensed for 124 beds but now has only about 50 of them occupied by residents.

Meanwhile, the pandemic created additional expenses in the form of staffing, protective gear, testing and other needs. Between lost revenue and higher costs, the pandemic imposed an additional financial burden of $4 million, on top of the $4 million Medicaid gap, JAA officials said.

“For nonprofit, faith-based caregivers like JAA, these financial losses in the nursing home business, year after year, are totally unsustainable,” Donald Shulman, president and CEO of the Association of Jewish Aging Services, a national advocacy group, said in a statement. “Therefore even the most resilient organizations are faced with making difficult decisions like this.”

RELATED: Quarantine sparks creativity for Mother’s Day celebrations

Staff writer JoAnne Klimovich Harrop contributed.