Whether you were born during the day or during the night, you weren’t born yesterday or last night, and the Secret Service claims that agents’ text messages before and during the attempted coup of Jan. 6 were inadvertently erased just don’t hold water.

The Secret Service told its agents to preserve phone messages as the agency phone system was being refreshed, and four House of Representatives committees had already sought the messages before they were deleted. But a warning was hardly necessary for anyone who even casually watches “Law & Order.”

Text messages are now widely known to be potential evidence in criminal proceedings. Deleting messages is a common attempt to cover up crimes.

The Secret Service began in 1865 as part of the Treasury Department. Its job was to protect the currency of the United States from counterfeiters. It was only after the assassination of three presidents — Lincoln, Garfield and McKinley — that the agency was charged with protecting the president, too.

Secret Service agents take an oath to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.” The few agents who are assigned to the presidential protective detail officially protect the presidency without regard to the holder of the office. While it is not part of their oath, agents understand that they could be called upon to sacrifice their own lives for their protectee’s life.

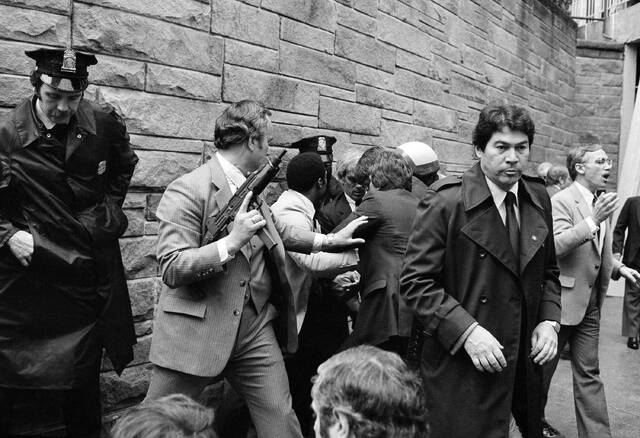

If you want to see what that looks like, watch the video of the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan in 1981. At the first sound of gunfire, Secret Service Agent Tim McCarthy turns squarely toward the shooter and makes his body as big as possible, taking a bullet in the stomach. McCarthy survived and was hailed as hero.

But there is nothing heroic about destroying potential evidence of a crime. That is true even if a close working relationship has grown into a friendship with the president. It is possible, in this case, that familiarity with a president may have bred contempt for the Constitution of the United States.

We have seen evidence disappear before when a president was being investigated. In 1973, President Richard M. Nixon’s loyal secretary Rose Mary Woods was transcribing the Watergate tapes and “accidentally” erased 18½ minutes of an Oval Office conversation between Nixon and his chief of staff. A laughable photo had Woods showing the contortions she had to undertake for it to happen as described.

It was another blow to Nixon’s credibility, and ultimately it served no purpose. Later, a different tape was released by court order, and it contained the “smoking gun” that proved Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate burglary cover-up. He resigned the presidency in 1974, and a number of his aides went to prison for trying to protect him.

Now, congressional investigators and the Justice Department have reason to suspect that these deleted text messages contain a “smoking gun.” Technical experts will work to recover the messages, the agents’ private phones could be examined and whistleblowers might be inspired to step forward.

That’s the thing with cover-ups. They are usually so ham-handed that they lead to a deeper dig for evidence and more people getting caught in the lies.