In the wake of the latest and perhaps the last coronavirus surge, big-city mayors are grappling with changes to every aspect of urban life. And nothing has changed more than most cities’ downtown districts.

What are threatened here are those revenue streams that pay for essential municipal and social services — those things that make a city a city.

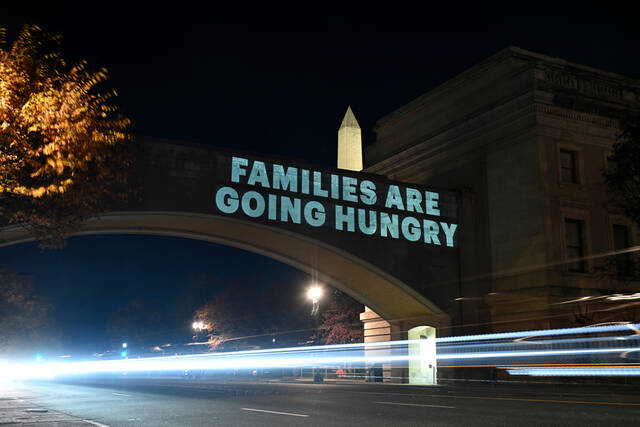

In her Washington Post column “Cities aren’t facing up to their ‘long covid’ crisis: Downtown is in deep trouble” last week, Megan McArdle wrote that “post-pandemic downtowns are likely to be short perhaps a quarter of their pre-pandemic workforce on an average day.”

“Empty streets and stores mean fewer jobs, lower taxes, higher costs and a risk that things will decay further. This problem also adds urgency to other issues that make it more unpleasant and less desirable to live in cities, like rising crime and public disorder,” McArdle wrote.

“Empty buildings attract crime and other nuisances, and they don’t create demand for the amenities that tenants look for when choosing an office. So each storefront or building that goes vacant will leach blight into the surrounding neighborhood.”

Luckily, Pittsburgh has had to fight for survival before, and we have won. With the city under great stress, we have a history of cooperating to save our town.

In 1946, when filthy air and polluted rivers threatened to leave Pittsburgh behind as the nation prospered, Mayor David L. Lawrence and Mellon Bank Chairman Richard King Mellon launched Pittsburgh’s first Renaissance. They cleaned up the environment and built Gateway Center and two parks — Mellon Square and Point State Park — all part of a new Downtown Pittsburgh.

In the late 1970s, Mayor Richard S. Caliguiri kept Pittsburgh nationally competitive through Renaissance II, partnering with the Allegheny Conference to change the Downtown skyline and recharge the city’s economy with six major buildings. And a safe Downtown became the region’s entertainment destination.

Both times, success came from strong partnerships with business and corporate leaders plus an aggressive approach to responsible development. Both times, the revenue from a healthy Downtown helped pay for services and improvements throughout the city’s neighborhoods and minimized the tax burden on residents.

Those same partnerships and bold action are needed now to get Pittsburgh through one more fight. Pittsburgh’s economic leaders will step up because they understand that Downtown is their neighborhood, too. Lawrence and Caliguiri counted on that.

Development in Downtown will look different this time. It will include the conversion and repurposing of some Downtown buildings for residential use. In the meantime, other developments throughout the city must move forward quickly and responsibly.

Those projects that have been delayed by bureaucratic bickering and demands that go far beyond the fairness of the public process are now the only hope we have to keep current homeowners from picking up the slack.

As cities struggle to fight off the lingering effects of covid on urban life as we once knew it, McArdle argues that we should remember what made our cities great in the first place.

“Before we can reimagine urban areas as models of ecologically sustainable living, or social justice, we have to reimagine downtown as what it used to be: the organic engine of a living city.”