As Pittsburgh City Council voted on how to divvy up $335 million in covid-19 relief money last week, the people of Wilkinsburg continued to wrestle with a proposal to merge their small town into Pittsburgh.

Small towns that are part of a metropolitan area have big-city problems. But they often lack big-city resources to fight those problems. And the size of that pool of emergency money showed the difference between Pittsburgh and the small towns that surround it.

Wilkinsburg, with a population of 15,930 according to the 2010 census, shares a boundary with Pittsburgh. It already uses Pittsburgh for fire protection and garbage collection, and Wilkinsburg’s middle and high school students attend Pittsburgh Public Schools.

As revenues have declined and costs increased and taxes have reached their limit, the borough has had to make hard choices. It is not an uncommon dilemma.

There are 130 municipalities in Allegheny County, and the economic shifts of the last 40 years mean that many of them are in the same tight spot. Some have successfully formed Councils of Governments and taken other measures, but many will inevitably be upside down financially.

If you have never lived in one of the old towns around Pittsburgh, it might be easy to say that an opportunity for better services and lower taxes through a merger is a no-brainer. But small-town living means more than that.

There is pride of place. These towns hold the hopes and dreams of all the families who ever lived there. And there are good people still living there who refuse to give up that identity.

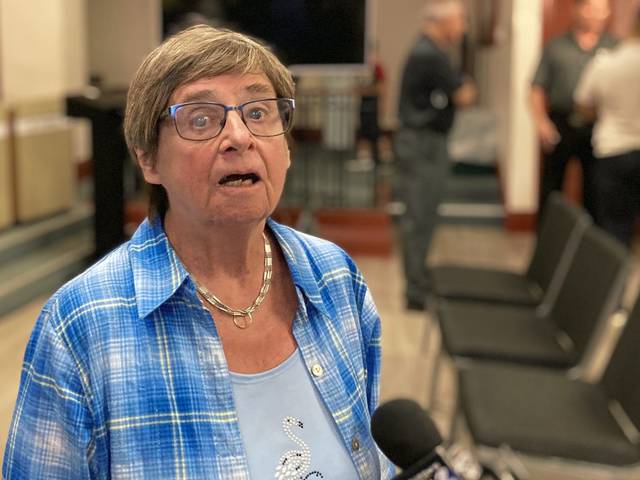

They have easy access to those who govern. Small-town elected officials and their constituents meet at the local grocery or while worshipping or taking an evening stroll.

And there is de facto community policing because they know each other. Even with a reliance on part-time officers, there is still a good chance that most small-town residents know the chief and the chief knows them.

But if the towns do merge, Wilkinsburg will always be Wilkinsburg. Pittsburgh is composed of strong and distinct neighborhoods — like Bloomfield, Manchester, Polish Hill and Greenfield — and Wilkinsburg would be celebrated with the rest.

And, while it may be less common to bump into elected officials in Pittsburgh than in a small town, each full-time Pittsburgh council member has resources — a staff and a budget and a focus on constituent service.

Finally, if done right, Wilkinsburg police officers will be kept in place until they retire or move on. But they will be bolstered by the expanded public safety services that Pittsburgh can provide.

These tough choices for Wilkinsburg and other struggling towns are not new. Since people started living in villages, social and cultural and economic changes have required changes in how we live and are governed.

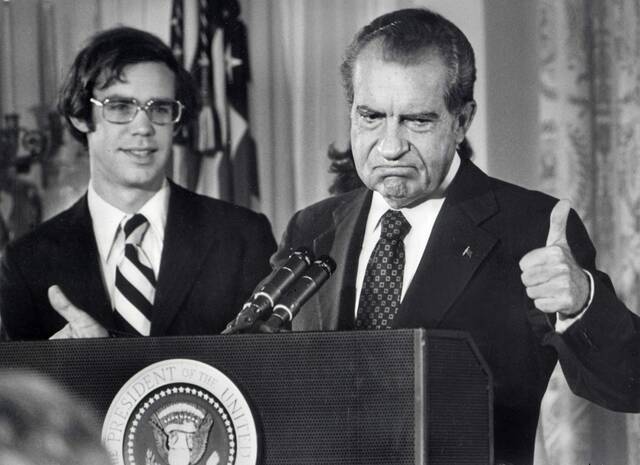

In Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s novel “The Leopard,” an old 19th-century Italian aristocrat fought changes in the form of government and the life that he knew, until he was told, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

It is the same choice facing struggling towns everywhere: what to give up to save those things that they value most.