DALLAS — For a couple of schools that will square off on the football field for only the third time in next week’s College Football Playoff opener, SMU and Penn State share a lot of history.

Starting with the 1948 Cotton Bowl, the first bowl game integrated. The second game, in 1978, a 26-21 Penn State win, was notable mostly because it furthered an undefeated regular season marred by a loss to Alabama in the Sugar Bowl.

But, if SMU partisans of a certain age harbor a grudge against the Lions, it’s not for anything that happened on a football field.

Only in the Associated Press poll that wrapped up the 1982 season, when, as the victims see it, Penn State stole SMU’s national title.

“There’s no way you can deny our team was a national champion that year,” Craig James told The Dallas Morning News in 2002. “I am totally convinced, after being on this side of the game and being an AP voter, that it was an emotional vote for Joe Paterno.

The consensus then was that SMU, coming off NCAA probation and a 10-1 season in 1981, had broken into big-time college football through a locked door. No other way to explain how a little private school with just seven winning seasons between 1950-80 suddenly would find itself smack in the middle of the nation’s best record over a four-year period.

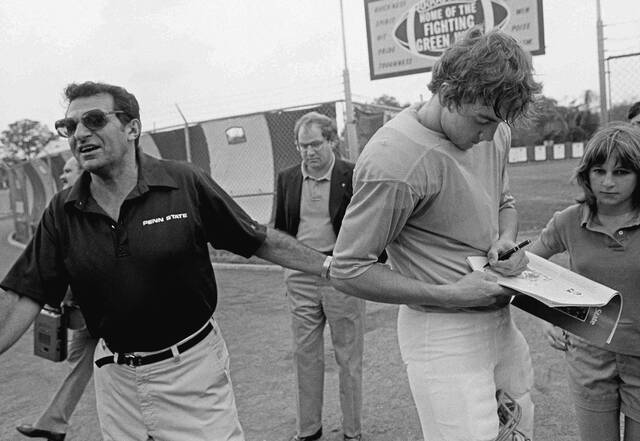

Contrast that image with Penn State’s Joe Paterno, patron saint of college football. Paterno had turned 56 only a week before the final poll came out in January 1983. There was a widespread belief that voters owed him after he had been denied in 1968, ‘69 and ‘73 despite undefeated seasons. Even though the Lions had lost badly to unranked Alabama and SMU’s only blemish was a 17-17 tie against an Arkansas team that would finish ninth, the prevailing sentiment was it might be Paterno’s last shot at his only title.

Whatever SMU had going for it in NFL-caliber talent, quality coaching and one of the greatest backfields in college football history, it sorely lacked in sentimental appeal.

“We were not gonna get the pity vote,” said Bob Condron, SMU’s sports information director at the time. “We were the enemy.”

Ron Meyer — who had recruited most of SMU’s stars, cultivated its flashy image and started it on the road to pride and perdition — left for the New England Patriots after the ‘81 season. In his place stepped Bobby Collins, an unlikely heir to such a vast fortune of talent. He came from Southern Mississippi, where he’d built a modest 46-32-2 record in his only head coaching job.

But he quickly would build a reputation as maybe the best coach in the Southwest Conference, a genteel Southerner with a knack for adapting to talent on hand.

Of course, it might have been a little tough to screw up SMU in ‘82. Of the players on a roster that included Michael Carter, Russell Carter and Wes Hopkins on defense, 19 would go on to play pro football. One is in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Eric Dickerson teamed with Craig James to form the famed Pony Express. With Lance McIlhenny at the reins, it was the most devastating 1-2 punch in college football.

“We thought we were as good as anybody,” McIlhenny said. “Every time we teed it up, we thought we could win.”

The Mustangs did just that, rising from eighth in the preseason poll to second by the time they played the Razorbacks in their final regular-season game. Along the way they escaped several close calls. None was more dramatic than the last-second kick return by Bobby Leach to beat Texas Tech the week before.

SMU didn’t have any such trick in its bag for Arkansas. Only after a controversial interference penalty did the Mustangs find themselves in a position to preserve their winning streak. Knowing he needed only a tie to win the SWC title, Collins elected to kick instead of going for two and the win. The media didn’t necessarily agree. The immediate reaction was to drop SMU from second to fourth and elevate Penn State to second. Some voters even cited Collins’ decision as justification for voting Penn State No. 1 and SMU No. 2 after the Lions beat top-ranked Georgia in the Sugar Bowl.

Besides beating the Bulldogs, Penn State had built a good case of its own. The Lions, led by Todd Blackledge and Curt Warner, had NFL talent, too. They were 5-1 against ranked teams. Their opponents’ composite record of 87-39-2 was tops in the nation, far ahead of SMU’s 56-66-2.

The separator, in Collins’ mind, was SMU’s status as the nation’s only undefeated team, while Penn State lost 42-21 to an Alabama team that would finish 8-4.

“I saw that game on television,” Collins told reporters, “and Alabama wasn’t very good this year.”

His argument didn’t go anywhere with voters. Penn State got 44 first-place votes to nine for SMU, which had finished its season by beating sixth-ranked Pitt and Dan Marino, 7-3, in a miserably cold Cotton Bowl. The Helms Athletic Foundation, in its last hurrah picking winners, split the title between Penn State and SMU, which was little consolation for the Mustangs.

Paterno felt their pain.

“I’ve been in that position,” he told reporters, “so I know what they are saying. But there is no question in my mind we are the No. 1 team.

“This is the best team we have had at Penn State.”

The sentiment wouldn’t hold long. Paterno’s 1986 team went 12-0, beating Jimmy Johnson’s No. 1-ranked Miami Hurricanes, 14-10, in the Fiesta Bowl. The win gave JoePa his second national title in four years.

Thaddeus Matula, SMU class of ‘01, remembers reading “National Champions” on the Cotton Bowl scoreboard after his beloved Mustangs beat Pitt in 1983.

What the 4-year-old didn’t understand was the question mark after it.

“That,” he said of the need for punctuation, “was a crime.”

Nearly 30 years later, Matula’s 2010 Peabody Prize-winning documentary, “Pony Excess,” detailed everything that led to the harshest sanctions on a football program in NCAA history. The film was “all about your blind spots,” Matula said. He noted the same could be said about what he called the “sympathy vote” for Penn State in ‘82.

Time has not been kind to Paterno or the school since. The defensive coordinator of the ‘82 Lions was Jerry Sandusky, now serving a 30- to 60-year sentence on multiple counts of sexually abusing boys. Paterno, whose knowledge of the allegations has been debated ever since, was fired after the charges in the fall of 2011 and died three months later at 85.

For the moment, McIlhenny likes the Mustangs’ chances against Penn State next week. As for whether a win over the Lions would make up for the ‘82 snub, McIlhenny isn’t sure such a thing would be possible. Neither is Matula, though, at the very least, he figures a win could be “cathartic” for him as well as others.

“Does one game make up for a serious miscarriage of justice?” he said. “No, but it does make for a good story.”